Retinal Tear and Detachment

Eye Care > Diseases of the Eye > Retinal Tear and Detachment

What is Retinal Tear and Detachment?

Retinal Tear

Retinal tears commonly occur when there is traction on the retina by the vitreous gel inside the eye. In a child’s eye, the vitreous has an egg-white consistency and is firmly attached to certain areas of the retina. Over time, the vitreous gradually becomes thinner, more liquid and separates from the retina. This is known as a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD).

PVDs are typically harmless and cause floaters in the eye; but in some cases, the traction on the retina may create a tear. Retinal tears frequently lead to detachments as fluids seep underneath the retina, causing it to separate and detach.

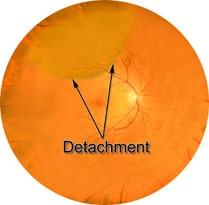

Retinal Detachment

A retinal detachment occurs when the retina’s sensory and pigment layers separate. Because it can cause devastating damage to the vision if left untreated, retinal detachment is considered an ocular emergency that requires immediate medical attention and surgery. It is a problem that occurs most frequently in the middle-aged and elderly.

There are three types of retinal detachments. The most common type occurs when there is a break in the sensory layer of the retina, and fluid seeps underneath, causing the layers of the retina to separate. Those who are very nearsighted, have undergone eye surgery, or have experienced a serious eye injury are at greater risk for this type of detachment. Nearsighted people are more susceptible because their eyes are longer than average from front to back, causing the retina to be thinner and more fragile.

The second most common type occurs when strands of vitreous or scar tissue create traction on the retina, pulling it loose. Patients with diabetes are more likely to experience this type.

The third type happens when fluid collects underneath the layers of the retina, causing it to separate from the back wall of the eye. This type usually occurs in conjunction with another disease affecting the eye that causes swelling or bleeding.

Signs and Symptoms

- Light flashes

- “Wavy,” or “watery” vision

- Veil or curtain obstructing vision

- Shower of floaters that resemble spots, bugs, or spider webs

- Sudden decrease of vision

Detection and Diagnosis

Retinal detachments are usually found because the patient calls the eye care practitioner’s office with a symptom listed above. It is critical that these problems are reported early, because early treatment can greatly improve the chance of restoring vision.

The eye care practitioner makes the diagnosis of a retinal detachment after thoroughly examining the retina with ophthalmoscopy. The retinal surgeon’s first concern is to determine whether the macula (the center of the retina) is attached. This is critical because the macula is responsible for the central vision. Whether or not the macula is attached determines the type of corrective surgery required and the patient’s chances of having functional vision after the operation.

Ultrasound imaging of the eye is also very useful for the retinal surgeon to see additional detail of the condition of the retina from several angles.

Treatment

There are a number of ways to treat retinal detachment. The appropriate treatment depends on the type, severity and location of the detachment.

Pneumatic retinopexy is one type of procedure to reattach the retina. After numbing the eye with a local anaesthesia, the surgeon injects a small gas bubble into the vitreous cavity. The bubble presses against the retina, flattening it against the back wall of the eye. Since the gas rises, this treatment is most effective for detachments located in the upper portion of the eye. In order to manipulate the bubble into the ideal location, the surgeon may ask the patient to keep his or her head in a specific position.

The gas bubble slowly absorbs over the next 1-2 weeks. At that time, an additional procedure is usually performed to “tack down” the retina. This can be done either with cryotherapy, a procedure that uses nitrous oxide to freeze the retina, sealing it in place, or with laser. Local anaesthesia is used for both procedures.

Some types of retinal detachments, because of their location or size, are best treated with a procedure called a scleral buckle. With this technique, a tiny sponge or band made of silicone is attached to the outside of the eye, pressing inward and holding the retina in position. After removing the vitreous gel from the eye with a procedure called a vitrectomy, the surgeon usually seals a few areas of the retina into position with laser or cryotherapy. The scleral buckle is not visible and remains permanently attached to the eye. This technique of reattaching the retina may elongate the eye, causing nearsightedness.

In rare cases where other types of retinal detachment surgeries are either inappropriate or unsuccessful, silicone oil may be used to reattach the retina. The vitreous gel is removed and replaced with silicone oil, which presses the retina into place. While the oil is inside the eye, the vision is extremely poor. After the retina has resealed itself against the back of the eye, a second procedure may be performed to remove the oil.

What you can do...

Early detection is the key in successfully treating retinal detachments and tears. Awareness of the quality of your vision in each eye is extremely important, especially if you are in a higher-risk group such as those who are nearsighted or diabetic. Compare the vision of your eyes daily by looking straight ahead and covering one eye and then the other.

Notify your doctor immediately if you notice any of the following:

- An obstruction of your peripheral vision (veil, shadow, or curtain)

- Sudden shower of floaters

- Light flashes

Illustrations by Mark Erickson

With acknowledgement to St. Lukes Eye Hospital.